This blog post is outdated

Here is the updated post: panic unreachable is unnecessary.Archived Post

In this Go Experience Report I am going to make a case for sum types over multiple return parameters.

Analysis of multiple return parameters

I wrote a little tool which does some analysis of Go source code. Thank you to the go/types library. The tool simply counts the number of times multiple return parameters are used. I ran this tool over the standard library and these are the results:

$ goanalysis std

functions with N return arguments:

-----------------------------

returns | number of functions

0 | 8693

1 | 7743

2 | 1975

3 | 205

4 | 25

5 | 4

6 | 1

7 | 1

-----------------------------

total number of functions: 18647

total number of functions with multiple return parameters: 2211

number of functions with 2 return arguments, where the second argument is an error: 1562

percentage of functions where multiple return parameters are really what we want: 3.480453

These results show us two things:

- most functions return zero or one argument.

- most functions with multiple return parameters return a value

andan error.

Only 3.5% of functions actually use multiple return parameters:

The tool does not count functions that return a value and an error as a proper use of multiple return parameters. This is because I think we should rather have sum types for this use case. I believe that most of the time we return:

- a value

anda nil error, or - a nil or zero value

anda non nil error

, which means that we would rather return a value or an error, than a value and an error.

For example:

func Atoi(s string) (int | error)Tuples are not first class citizens

In the go/types library I found that multiple return parameters are actually called Tuples, but these Tuples are not first class citizens. For example nested tuples are currently not supported:

func() ((string, error), error)I ran into this while building monadic error handling in goderive. I worked around this by using a function:

func() (func() (string, error), error), which is not ideal, since a function implies some computation. We currently also cannot directly pass multiple return parameters to a function:

func f() (int, error) {

return 1, nil

}

func g(i int, err error, j int) int {

if err != nil {

return 0

}

return i + j

}

func main() {

i := g(f(), 1)

println(i)

}This gives us the following error:

prog.go:15:11: not enough arguments in call to g

prog.go:15:13: multiple-value f() in single-value contextWhat are sum types

A sum type has many names including: tagged union, oneof or sealed trait.

It is a way to represent a disjoint union of types in a single type.

Say for example we have the sum type (int | bool).

This sum type will be able to represent all possible int values plus all possible bool values.

The advantage of sum types are that the compiler is able to tell whether you handle all the disjoint types. This means that checking an error can be enforced by the compiler and that a type switch can be less error prone and allow the compiler to make sure that you handle all cases.

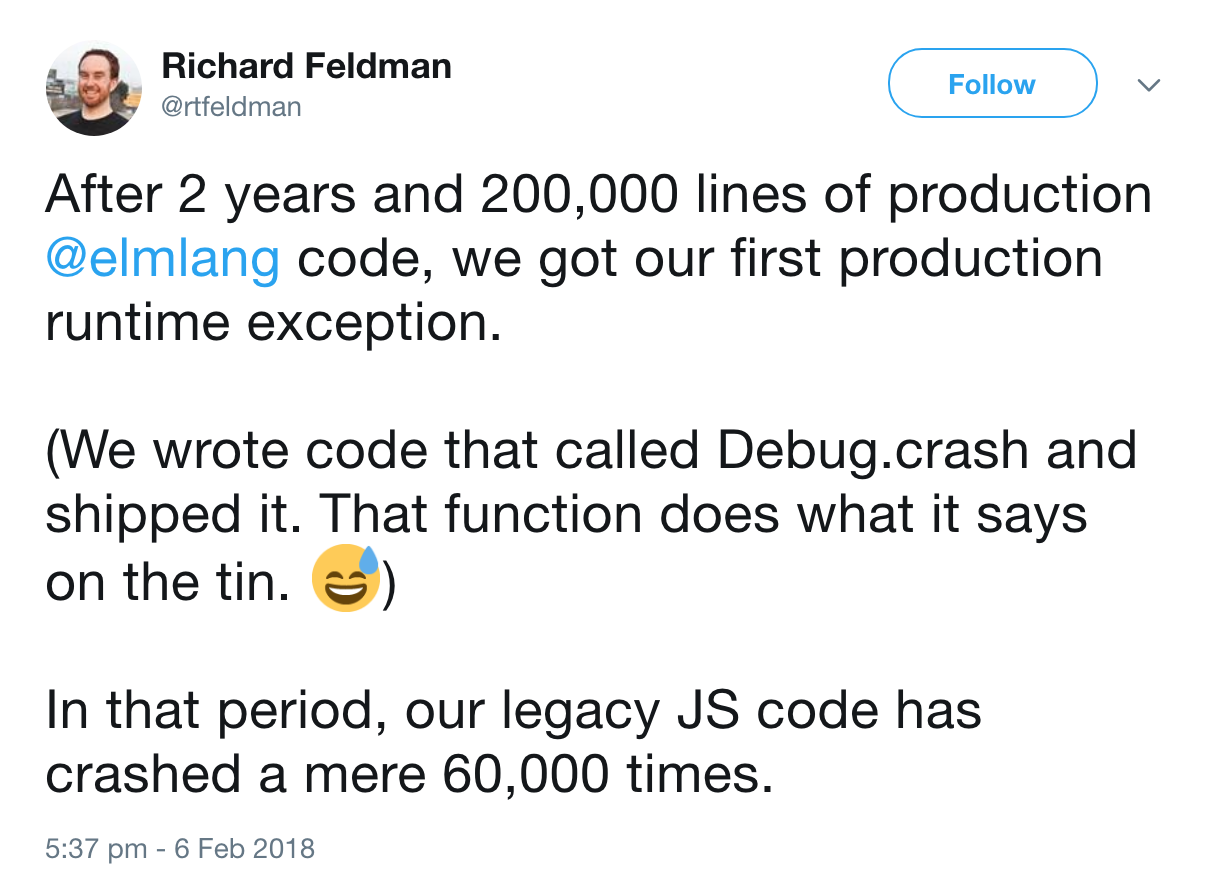

Sum types is how Elm can eliminate all possible runtime errors:

But wait, I thought the most common runtime exception was a null pointer exception.

Yes, technically a pointer is also a sum type.

It can have all the values of the pointer type plus one for null.

Elm, Haskell, etc. has a Maybe type, which is used to represent these types of values.

The same as a pointer, it can represent Just the value or Nothing for null:

data Maybe a = Just a | NothingThese days even Java has something similar called Optional.

This enables the compiler to enforce you to do a “null” check and avoid null pointer exceptions.

We need sum types

Firstly, we need sum types to return a value or an error, instead of a value and an error from functions, but we need sum types for other reasons as well.

In my validation language, Relapse’s Abstract Syntax Tree, each Pattern can be one of several Patterns:

type Pattern struct {

Empty *Empty

TreeNode *TreeNode

LeafNode *LeafNode

Concat *Concat

Or *Or

And *And

...Here I simulate a sum type with a struct which has several fields (a product type) where only one field should be non nil. This is not ideal in terms of type safety. For instance when writing a function that processes a pattern, I have to do a nil check for each field:

func Nullable(refs ast.RefLookup, p *ast.Pattern) bool {

if p.Empty != nil {

return true

} else if p.TreeNode != nil {

return false

} else if p.LeafNode != nil {

return false

} else if p.Concat != nil {

return Nullable(refs, p.Concat.GetLeftPattern()) &&

Nullable(refs, p.Concat.GetRightPattern())

} else if p.Or != nil {

return Nullable(refs, p.Or.GetLeftPattern()) ||

Nullable(refs, p.Or.GetRightPattern())

} else if p.And != nil {

return Nullable(refs, p.And.GetLeftPattern()) &&

Nullable(refs, p.And.GetRightPattern())

...This is fine, but when I add a new pattern the compiler is not going to tell me that I forgot to update one of these functions.

I opted for another implementation, using a type switch, but it only works because each field is of a unique type and I still have the runtime type check problem.

In my opinion this makes Go a strong dynamically typed language, rather a strong statically typed language, which I would prefer to use.

The use of an interface as a way to simulate a sum type can also be found in a Protocol buffers library for Go where they have to implement oneof.

From this proto message:

message MyMessage {

oneof BoolOrInt {

bool BoolValue = 1;

int32 Int32Value = 2;

}

}The following go code is generated:

type MyMessage struct {

BoolOrInt isMyMessage_BoolOrInt

}

type isMyMessage_BoolOrInt interface {

isMyMessage_BoolOrInt()

}

type MyMessage_BoolValue struct {

BoolValue bool

}

type MyMessage_Int32Value struct {

Int32Value int32

}

func (*MyMessage_BoolValue) isMyMessage_BoolOrInt() {}

func (*MyMessage_Int32Value) isMyMessage_BoolOrInt() {}This implementation is far from ideal, in my and others’ opinion.

In an alternative Protocol buffer library for Go, developers cannot even agree on what they would really like to have as a oneof implementation in Go, because Go does not lend itself to sum types.

A need for sum types can also be found in the go/ast library, where ast.Spec is documented to be one of the following types:

*ImportSpec*ValueSpec*TypeSpec

This is something that could have been enforced by the compiler, instead of mere documentation.

Another example is the Walk function, which ends with a classic runtime error, where a compile error would have been more appropriate:

default:

panic(fmt.Sprintf("ast.Walk: unexpected node type %T", n))

}Everyone else has it

Sum types is not a new language feature, but a very old one. Algol 68 first introduced united modes (sum types) in the 1960s. This has been adopted by Pascal, Ada, Modula-2 as variant records. Later Haskell, ML and now Scala, Elm, Rust, Swift, F#, Protobufs and even C++ have adopted sum types. Even Java has announced plans to also add sum types. I do not know why we were forced to write error prone code when a solution has existed, but I hope it can be fixed.

Conclusion

I have shown that multiple return parameters are overrated, since:

- it is rarely used for the right reason and

- it is not even a first class citizen.

I have also demonstrated several use cases for sum types:

- proper error handling

- in the implementation of languages, and

- protocol buffers

There are MANY more use cases, including avoiding null pointer exceptions.

I think a Go without multiple return parameters and with first class sum types would make for a better language.

Thank you

- Sjoerd Dost for proof reading and pushing me to write this Go Experience Report.

- Gustav Paul for proof reading and making me believe this was worth upgrading from a gist to a blog post.

- Petr Bouda for proof reading and keeping me up to date with the future of Java.

- Yigal Duppen for proof reading.